Social Determinants of Health: Their Relation to Vision, Aging, and Advocacy

Healthy People 2020 Graph of SDOH Areas. Reprinted from Healthy People 2020, n.d. Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Copyright 2022. Reprinted with permission.

Healthy People 2020 Graph of SDOH Areas. Reprinted from Healthy People 2020, n.d. Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Copyright 2022. Reprinted with permission.

Consider typical concerns throughout your life. You worry about where to live, how to pay your bills, your health and medical bills, receiving an adequate education, and remaining socially connected. Reflect on how these concerns will affect you as you grow older and begin to experience health issues. These considerations form the basis of this article and demonstrate the critical importance of these factors as we age.

Unfortunately, the needs and circumstances of older people experiencing age-related vision loss are too often ignored by policymakers, service providers, and even the public. The situation has evolved into an emerging crisis that is playing out on a national scale and a very personal scale. The result is that individuals and families are trying to cope with age-related vision loss without the knowledge of vision rehabilitation services and/or the ability to access them due to a lack of funding and personnel shortages.

A study in 2021 (Rein et al.) of the economic burden of vision loss (VL) clearly shows this lack of attention to the realities of vision loss as a public health crisis. According to the authors,

“We estimated an economic burden of VL of $134.2 billion: $98.7 billion in direct costs and $35.5 billion in indirect costs. The largest burden components were NH [nursing homes] ($41.8 billion), other medical care services ($30.9 billion), and reduced labor force participation ($16.2 billion), all of which accounted for 66% of the total. Those with VL incurred $16,838 per year in incremental burden. Informal care was the largest burden component for people 0 to 18 years of age, reduced labor force participation was the largest burden component for people 19 to 64 years of age, and NH costs were the largest burden component for people 65 years of age or older…. (Rein et al.,2021)”.

With these factors in mind, this article covers the social determinants of health as they apply to older people with declining vision, the implications for individuals and society, and advocacy efforts to mitigate and improve the outlook for older people experiencing blindness or low vision in this country.

What are Social Determinants of Health (SDOH)?

According to the World Health Organization, “Social Determinants of Health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age (SDOH-global, 2022).”

The five key areas included in the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH):

- Economic Stability

- Education

- Social/Community Context

- Health and Health Care

- Neighborhood and Built Environment

SDOH for Older People

The selection of SDOH as a leading health topic recognizes these five key areas’ critical roles in everyday life. (Social Determinants of Health, 2022). Let’s review how each role can impact older individuals who are blind or low vision.

Economic Stability

Socioeconomic status, measured as higher income, higher educational status, or non-manual occupational social class, was inversely associated in the Healthy People 2020 data with the prevalence of blindness or low vision (Social Determinants, 2022). Further, the Big Data Project results, recently initiated by Aging and Vision Loss Coalition (discussed later), substantiate these findings.

Education

The Big Data National Report (2022), indicates that “Among older people with blindness or low vision, 27.8% did not complete high school compared to 12.5% of people without blindness of low vision.” (United States, p. 10, 2022) Results are similar in the individual state reports. For example, 34% of older people who are blind or low vision in Louisiana did not complete high school compared to 16% of those who are sighted (Louisiana, 2022).

Social and Community

Having community-based resources and transportation can positively affect the health status of older people. Studies have indicated that increased levels of social support are associated with a lower risk of physical disease, mental illness, and death (Morbidity, 2005).

Health and Health Care

Health inequities are related to Social Determinants of Health based on gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, race, geographic region, or health conditions. According to Varma et al. (2016), women are projected to outnumber men by 30 to 32 percent concerning low vision and 6 to 11 percent concerning blindness. This is attributed to women’s higher prevalence and longer life expectancy than men. Additionally, women are less likely to be treated for conditions, including blinding eye diseases like glaucoma (Varma et al., 2016). Varma also found that African American individuals experienced the highest prevalence of low vision and blindness. But by 2050, the highest prevalence of blindness/ low vision among minorities will shift from African Americans to Hispanics.

Older people who are blind or low vision have a higher rate of other health conditions, such as diabetes and stroke (NHIS, 2018). Also, according to research by Swenor (2019), older people with vision loss have a greater risk of dementia, cognitive decline, and cognitive impairment.

Coupled together, these conditions can cause life-threatening situations. For example, being at risk of vision loss and chronic health conditions such as hearing loss, living alone without access to home modification, lack of transportation, limited vision rehabilitation services, and lack of assistive technology can compound with severe consequences, as evidenced by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Inability to Navigate Heath Care and Find Vision Rehabilitation Services

Issues for older people who are blind or low vision include the inability to navigate the health care system and the general lack of knowledge about and difficulty locating vision rehabilitation services. Often doctors do not refer patients to rehabilitation services; older people who are blind or low vision may go years without knowledge of such services.

Health Literacy and Medication Management

Another issue is health literacy, including managing medications and medication information, which can cause major medical errors. The American Pharmacists Association says that problems related to medications and their mismanagement are estimated to lead to 1.5 million preventable adverse events yearly, resulting in 177 billion dollars in injury and death (Medication, n. d.).

Additional Issues Related to Low Vision and Blindness

SDOH and COVID-19

Evidence reveals social and economic factors contribute to COVID-19 outcomes. For example, increased severity is related to social conditions that increase the prevalence of pre-existing medical conditions and decreased access to health care (Bonotti & Zech, 2021). In addition, the pandemic has affected self-determination, which also affects the quality of life and is restricted by the effects of the virus. As noted in AFB’s Flatten Accessibility Survey, people with vision loss have an even harder time being able to make decisions about how they’re going to obtain necessities such as food and medical attention, vaccinations, and testing for COVID-19 (Rosenblum et al., 2020). Thus, the pandemic has made a major, negative shift in Social Determinants of Health and its effect on people with vision loss (COVID-19, 2020).

Falls and Fracture Risk

A study by Monaco et al. (2016) indicated that falls and fracture risk are significantly higher in people with vision loss and very costly. According to AARP (Allen, 2018), “A substantial share of healthcare expenditures for adults aged 65 and older was attributable to falls, accounting for 6% of Medicare expenditures & 8% of Medicaid costs. Of the $50 billion, almost 99% was spent in the aftermath of nonfatal falls.”

Risk of Depression

Individuals who are blind or low vision are at higher risk for depression and often do not receive needed mental health services. “[F]or every dollar spent treating depression, an additional four dollars and seventy cents is spent on the direct and indirect cost of related illnesses, and another dollar ninety is spent on a combination of reduced workplace productivity and the economic cost associated with suicide directly linked to depression” (Greenberg et al., 2015). Read more about depression and its effects.

Social Isolation

Social isolation contributes to depression and was exacerbated by the pandemic. Lack of social relationships is a significant risk factor for health, rivaling health risk factors such as cigarette smoking, blood pressure, blood lipids, obesity, and physical activity. Alarmingly, the health risk of prolonged isolation is equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes a day (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). A loss of social connections can increase the risk of death by at least 50 percent and, in some cases, by more than 90 percent. Lonely people are more prone to depression (Raypole, 2020). Also, loneliness and low social interaction predict suicide in older people (O’Connell et al., 2004).

Transportation

Transportation has always been a major issue for people who are blind or low vision. However, the pandemic exacerbated the options for non-drivers and demonstrated how very vulnerable people are when transportation is even more curtailed. As noted in AFB’s position paper, the Journey Forward, “81% of the respondents (In Flatten Inaccessibility study), agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “I am concerned that because I do not drive, I will not be able to get myself or a family member to a hospital or healthcare facility if they have severe COVID-19 symptoms,” and 79% agreed or strongly disagreed with the statement, “I am concerned that because I do not drive, I will have difficulty getting groceries or other key essentials.” (Journey Forward, 3rd paragraph, 2020).

Technology

As reinforced during the pandemic, the ability to use smartphones and other technology has made a significant difference in the lives of people with the technology and skills to use it. We have seen that technology has been used for telehealth, support groups, vision rehab training, grocery shopping, and going to church. Being able to obtain and use technology effectively has become even more important.

Limited vision rehabilitation services, including a lack of assistive technology (AT) and training to use it have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

Public Attitudes about Eye and Vision Health

Public attitudes about eye and vision health are an additional issue facing older people who are blind or low vision. A study by Scott et al (2016) found that regardless of the ethnicity of the people answering the survey, participants thought losing eyesight would potentially have the greatest effect on their day-to-day life. After losing eyesight came losing memory, limbs, speech, and hearing.

People new to blindness/ low vision are part of the general public. These attitudes impact how people losing vision feel about themselves and contribute to the fear of vision loss and identification as a person with vision problems.

Healthy People 2030

As a part of the Healthy People Initiative, the National Eye Health Education Program (NEHEP) proactively addresses the social determinants of health and people who are blind or low vision. Healthy People 2030 builds on lessons learned during the first four decades of the Healthy People programs. Unfortunately, the U.S. lags behind other developed countries on key measures of health and well-being despite us spending the highest of our gross domestic product on health (Live Science, 2010).

Healthy People 2030 has the following goals: attain healthy, thriving lives and well-being, free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death; eliminate health disparities, achieve health equity; attain health literacy to improve the health and well-being of all; create social, physical, and economic environments that promote attaining full potential for health and well-being; promote healthy development, healthy behaviors, and well-being across all life stages; engaging leadership, key constituents, and to take action and design policies that improve the health and well-being of all (Healthy People 2030 Framework, 2022).

Role of Vision Rehabilitation in Healthy People 2030

The vision rehabilitation objectives (found in the sensory section) include challenges with vision, hearing, balance, smell, taste, voice, speech, or language, focusing on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of these disorders.

The core objectives for vision include reducing vision loss through treatment and timely care and increasing the number of individuals receiving vision rehabilitation and assistive devices. NEHEP has set outcomes for these objectives as described below.

Demographics and Statistics—What They Tell Us

The field of vision rehabilitation has labored for decades without good data to inform our work and our policy and advocacy efforts. We now have several surveys to determine the number of older people with vision problems in the United States. However, each survey is conducted differently, and the questions vary—a point critical to our understanding of the population and its needs.

Survey of Residents with Vision Loss in Long-Term Care

The population studies cited below are based on individuals living in communities and do not include residents of long-term care facilities. Monaco et al. (2021), published the results of a seminal study done in 20 nursing homes in Delaware, showing that, “The overall prevalence of low vision or blindness was 63.8% and was above 60% for each age, sex, and race category.” (p.1) The authors state that “National attempts to promote vision and eye health among institutionalized residents have largely been unsuccessful.” (p.2)

This study points out the real need for comprehensive vision care, which includes a complete understanding of the risks for long-term care and the quality of life for individuals who are blind or low vision living in these facilities. For example, are older people with undiagnosed vision loss consigned to these facilities in lieu of receiving eye care and or vision rehabilitation services that could enable them to live in a less restrictive environment? (Monaco et al., 2021).

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), used to determine the outcomes of Healthy People 2030, is an annual survey of the civilian, non-institutionalized population. This survey does not include people who are in nursing homes. They ask the vision-related questions: “Do you have trouble seeing even when wearing glasses?” and “Are you blind or unable to see at all?” Data from the National Health Interview Survey in 2018 indicated there are 12.4 million older people, 60 years of age and older, with vision trouble (IPUMS-NHIS Survey, 2018).

In 2020, the number of individuals surveyed who sought vision rehabilitation services was 4.3 percent of adults 18 and older with vision loss. The target for 2030 is 6.2%. For assistive and adaptive devices, the baseline is 12.4 percent of adults 18 years of age and older, and the target is 15.9% (Healthy People 2030, 2022). These numbers are extremely low in comparison to the size of the population.

American Community Survey (ACS)

The American Community Survey (ACS) is an annual census-related survey of the civilian, non-institutional population. This survey asks the vision-related question: “Is this person blind or does he or she have serious difficulty seeing even when wearing glasses?” (How, 2021).

According to the ACS, 2018, 7.58 million adults 18 and older had vision difficulty. That number represented 2.4 percent of the population of that age group (ACS, 2018).

The American Community Survey includes other disability questions such as hearing difficulty, cognitive difficulty, ambulatory difficulty, self-care difficulty, and independent living difficulty. For example, in 2018, 25 percent of people with cognitive difficulties had vision difficulty; 22 percent with independent living difficulties had vision difficulty; and 18 percent with ambulatory issues had vision difficulty (ACS, 2018). Based on a five-year breakdown by age from 2014 to 2018, the highest percentage of vision difficulty was 21 percent for people over 90 and 13 percent for people aged 85 t, and 9% for people aged 80-84 (Sheffield, 2020).

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is conducted by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and collects state data about US residents regarding their health-related risk behaviors, chronic health conditions, and preventative services use. BRFSS was established in 1984 in 15 states and is now completed in all 50 states. The CDC completes more than 400,000 telephone interviews with adults each year, making it the largest continuously conducted health survey system in the world. The vision-related question they ask annually is the same as the ACS, “Are you blind, or do you have serious difficulty seeing even when wearing glasses?” (Vision, 2017).

Through the survey, data sets are available showing the prevalence rates in different parts of the country by state and county. Thus, the data provides especially useful information for planning services and geographical distribution.

VisionServe Alliance uses the BRFSS survey, coupled with the ACS, in their Big Data Project to provide states with specific information about their population of older people who are blind or have serious difficulty seeing. Although data has been assembled for only 8 states thus far, the study highlights major geographic differences in the prevalence of blindness/ low vision in states and within counties. Further, in looking at the negative effects of low vision and blindness, it’s critically important to track the number and characteristics of individuals with low vision and blindness. It’s especially important, given the negative effect of these conditions on physical and mental health. Individuals who are blind or low vision have a higher risk of chronic health conditions, unintentional injuries, social withdrawal, depression, and mortality and how these relate to the social determinants of health (Varma et al., 2016).

National Advocacy Efforts

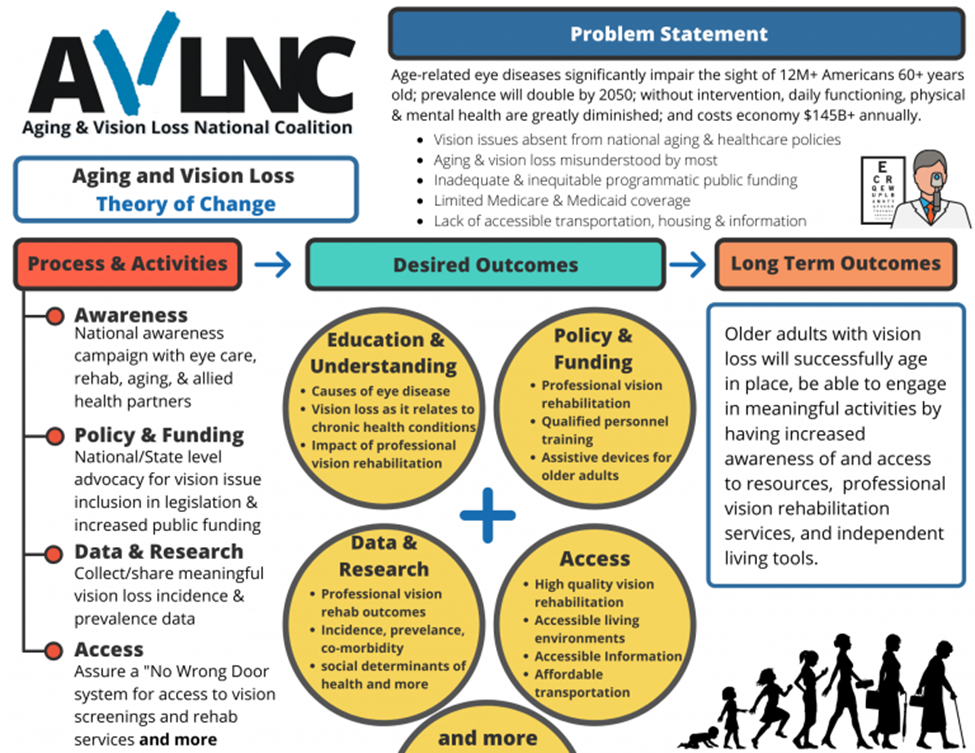

Aging and Vision Loss National Coalition

Enter the Aging and Vision Loss National Coalition. Dismayed the number of older people going without vision rehabilitation and needing other services to ameliorate declining vision, the Aging and Vision Loss Coalition was formed in 2020. The Coalition has taken up the banner as champions for older people with vision loss, with a theory of change that embraces the following premises:

“In order to be Effective, Policies, Practices, and Systems in Support of Older People Living with Blindness & Low Vision must be:

- Included in social determinants of health acknowledging the unique risks of aging with vision loss

- Developed in collaboration with experts & older people skilled in self-advocacy

- Culturally competent

- Equitably funded” (VisionServe, n.d.).

AVLNC Theory of Change

AVLNC Theory of Change

Note: Theory of Change infographic. Reprinted from VisionServe Alliance, n.d. Retrieved from https://visionservealliance.org/avlnc/. Copyright 2022. Reprinted with permission.

The coalition has developed four goals that coincide with many of the social determinants of health.

Public Awareness—The coalition seeks to educate the public and professionals about vision loss and change public perceptions.

Data and Research—the coalition has initiated a Big Data project, described in depth in Big Data is a Big Deal for Older People with Vision Loss (Murphy, 2022), using the BRFSS survey described above.

Access to Quality Vision Rehabilitation Services—the coalition has completed a toolkit for aging service providers to enable them to provide more informed services and access for older people who are blind or have low vision.

Policy and Funding—the coalition is working on funding of services and a comprehensive piece of legislation that will improve the lives of older people with vision loss through greater access to vision rehabilitation and other needed services such as transportation.

Consumer Advocacy—the coalition has a working group on developing a consumer advocacy training program. Find out more about this project.

In summary, older people with vision loss are affected by the SDOH in major ways that are life-threatening and critical to address:

- Being at risk of vision loss & chronic health conditions, such as hearing loss

- Being in a low socio-economic status

- Living alone without access to home modification

- Lack of transportation

- Limited vision rehabilitation services, including a lack of assistive technology (AT) or knowledge of how to use it, are all exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Only by effecting real systems change can we hope to move the needle and improve the quality of life for older people experiencing low vision or blindness. Join the AVLNC advocacy efforts to help effect critical change and improve quality of life.

Additional Information

This document was excerpted in part from How Social Determinants of Health Relate to Vision and Aging (instructure.com) (OIB-TAC) by Priscilla Rogers, Ph.D.

Vision_Rehabilitation and Aging Brief Final_12.14.20.docx (live.com)

References

Anderson, G. O. & Thayer, C. (2018). Loneliness and social connections: A national survey of adults 45 and older. AARP. https://doi.org/10.26419/res.00246.001

Allen, K. (2018). Older adult falls cost about $50 billion a year. AARP. https://www.aarp.org/health/conditions-treatments/info-2018/medicare-fall-costs-fd.html

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. (2021). Behavioral Risk Factors – Vision and Eye Health Surveillance [Data set]. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://chronicdata.cdc.gov/Vision-Eye-Health/Behavioral-Risk-Factors-Vision-and-Eye-Health-Surv/vkwg-yswv

Bonotti, M., & Zech, S. T. (2021). The Human, Economic, Social, and Political Costs of COVID-19. Recovering Civility during COVID-19, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-6706-7_1

COVID-19 – what we know so far about… Social determinants of health. (2020). Public Health Ontario. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/ncov/covid-wwksf/2020/05/what-we-know-social-determinants-health.pdf?la=en

Greenberg, P. E., Fournier, A. A., Sisitsky, T., Pike, C. T., & Kessler, R. C. (2015). The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(2), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14m09298.

Hayes, K. (2017). Slips and falls can be deadly. AARP. Slips and Falls Around the Home Can Be Deadly (aarp.org).

Healthy People 2030. (n. d.). Increase the use of vision rehab services by people with vision loss–V-08. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/sensory-or-communication-disorders/increase-use-vision-rehab-services-people-vision-loss-v-08.

Healthy People 2030 Framework. (2022). Healthy People 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People/Development-Healthy-People-2030/Framework.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspectives on psychological science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(2):227-37. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25910392/.

How disability data are collected from the American community survey. (2021). Census. https://www.census.gov/topics/health/disability/guidance/data-collection-acs.html

Journey Forward: Transportation and Moving Through Public Space. (2020). American Foundation for the Blind. https://www.afb.org/research-and-initiatives/covid-19-research/journey-forward/transportation-moving-through-public

Live Science. (2010). U.S. last in health care among 7 industrialized countries. https://www.livescience.com/8356-health-care-7-industrialized-countries.html?msclkid=2055aa05bfea11ec8f71a59dc5c5f221.

Louisiana’s older population and vision loss: A briefing. (2022). VisionServe Alliance. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1bhQMi1YxDB5pMglE5OllqwQ_oMKZ_-9F/view

Medication Therapy Management (MTM) Services. (n. d.). APhA. https://www.pharmacist.com/Practice/Patient-Care-Services/Medication-Management

Monaco, W. A., Crews, J. E., Nguyen, A., & Arif, A. (2021). Prevalence of vision loss and associations with age-related eye diseases among nursing home residents aged ≥65 Years. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 22(6), 1156–1161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.08.036

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. (2005). Social support and health-related quality of life among older adults—Missouri, 2000. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5417a4.htm

Murphy, L. (2022). Big data is a big deal for older people with vision loss. Big Data is a Big Deal for Older People with Vision Loss – ConnectCenter (aphconnectcenter.org)

Raypole, C. (2020). Loneliness and depression: What’s the connection? Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/loneliness-and-depression#coping-with-loneliness

Rein, D. B., Wittenborn, J. S., Zhang, P., Sublett, F., Lamuda, P. A., Lundeen, E. A., & Saaddine, J. (2021). The economic burden of vision loss and blindness in the United States. Ophthalmology, 129(4), 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.09.010

Rosenblum, L. P., Chanes-Mora, P., McBride, C. R., Flewellen, J., Nagarajan, N., Nave Stawaz, R., & Swenor, B. (2020). Flatten inaccessibility: Impact of COVID-19 on adults who are blind or have low vision in the United States. American Foundation for the Blind. AFB_Flatten_Inaccessibility_Report_Revised-march-2022.pdf

Scott, A. W., Bressler, N. M., Ffolkes, S, Wittenborn, J. S., & Jorkasky J. (2016). Public attitudes about eye and vision health. JAMA Ophthalmology. 134(10):1111–1118. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.2627

Sheffield, R (2020) Access to Demographic Data: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (University of Minnesota): https://www.ipums.org/ : American Community Survey (IPUMS-USA); National Health Interview Survey (IPUMS_IHIS)

Social determinants of health. (2022). Healthy People 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health

Social determinants of health – global. (2022). World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/.

Varma R., Vajaranant T. S., Burkemper B., Wu, S., Torres, M., Hsu, C., Choudhury, F., & McKean-Cowdin, R. (2016). Visual impairment and blindness in adults in the united states: Demographic and geographic variations from 2015 to 2050. JAMA Ophthalmology.

Vision and Eye Health Surveillance System. (2017). Center for Disease Control and Prevention

United states’ older population and vision loss: A briefing. (2022). VisionServe Alliance. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1HaHR7zJCUwaGri6pX5jbFBbw51ZnNeVm/edit

VisionServe Alliance. (n. d.). Aging & vision loss national coalition. https://visionservealliance.org/avlnc/