A Myopic View

Myopia or nearsightedness is a condition I’ve lived with all of my life. Being able to see things at an extremely close distance, but not see things far away, was normal for me and I successfully managed living with myopia most of my life through the benefit of corrective lenses.

The first time I heard I had high myopia, a rare inherited type of nearsightedness, I was in my 30s. Since my ophthalmologist seemed unconcerned about the condition I took the same approach and continued with my yearly eye examinations and receiving new lenses at each visit. I should probably mention that every time I put on a new pair of contact lenses and/or eyeglasses the world for me became a magical place because suddenly everything came into a crisp, clear view.

What I didn’t understand about my high-myopic eyes was that instead of being round, they were extremely long, like a football. This lengthening of my eyes stretched my retinas (located at the back of the eye) and would later result in my battling to retain my eyesight.

Plunged Into The World Of Sight Loss

It’s a little ironic to me that as a person who literally lived their entire life focused on things close up that I could miss what was directly in front of them. However, a part of me now thinks that taking a myopic approach to my looming sight loss was a coping mechanism.

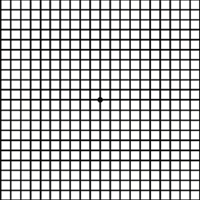

My sight loss journey spanned four years and began instantaneously with the development of a macular hole. The first time an ophthalmologist told me “I’m sorry there is no more that can be done for you” was during an emergency appointment when I was diagnosed with that first macular hole. At this visit, among other tests, the doctor introduced me to a tool called an Amsler grid (a square containing a grid pattern).

Amsler Grid

Amsler Grid

The Amsler grid would help the doctor to check my central vision loss. When I looked at the grid with my affected eye, instead of the lines being perfectly straight they were warped and I couldn’t see the center. As a matter of fact, everything I looked at with the eye appeared like a funhouse mirror or a kaleidoscope. I couldn’t make sense out of anything I was seeing and the kicker was I wouldn’t have even noticed it without a contact lens in the eye because of my myopia.

As my sight continued to decline during that four-year period, I had several vitrectomies (surgical procedures to repair the macular holes and restore my central vision). My retina specialist came highly recommended and I felt safe and secure in his hands. He explained to me before my first vitrectomy that all the numbers were in my favor and he believed my sight could be fully restored. Additionally, he said because of my age and other factors he didn’t think I’d have to worry about having issues with my unaffected eye.

Unfortunately, that first macular hole set off a chain of events that led to additional macular holes, a detached retina, cataracts, ocular hypertension, uveitis, retinal hemorrhage, and eventually a glaucoma diagnosis. My eyes were subjected to pokes, prods, lasers and on one occasion my doctor injected a gas bubble in my eye during an office visit to repair an epiretinal membrane.

From Rescue To Recovery

Whenever a person goes missing and the mission turns from rescue to recovery my heart breaks. I’m not sure if this analogy fits the scenario of the doctor/patient relationship when things don’t go as planned but my retina specialist could not let go. From 2005 up through 2009 he fought to restore my sight almost inadvertently to my detriment.

2007 was especially challenging because in addition to my sustained ocular hypertension (pressure in the eye is higher than normal), I developed an epiretinal membrane in my good eye that advanced to a Stage II macular hole. Then later that year I went to Cleveland Clinic for a second opinion and required emergency laser surgery to repair a detached retina.

The final failed vitrectomy leading up to my legal blindness status resulted in a retinal hemorrhage. Deep inside of me, I knew this was the defining moment in my sight loss story. Before I took one last trip back to Cleveland Clinic for another opinion I told my retina specialist I wanted to learn how to use the white cane.

Hanging onto the hopes that my sight would return was exhausting. As a realist, I was ready to move onto the next chapter of my life through the recovery phase. I was a little hurt that my retina specialist wasn’t on board as his response to my white cane inquiry was “that would be a tragedy.”

Glaucoma A Hidden & Diabolical Disease

In view of my eye issues, different surgeries, and procedures I endured, my doctors agreed not to diagnose me with glaucoma for months. The action plan was to put me on a pressure-lowering medication on a trial basis then they would measure outcomes.

Xalatan was the first medication I was prescribed and it worked extremely well. This particular medicine is effective because it increases the outflow of the fluid inside the eye. Unfortunately, after the trial period ended and I was taken off the drops, my pressure increased exponentially. At this point, my retina specialist diagnosed me with open-angle glaucoma and put me on two different medications.

After Cleveland Clinic declared me legally blind my glaucoma follow-up care was handled by another ophthalmologist whom I’ve seen since 2008. With the exception of one time for 11 years, I adhered to my doctor’s instructions, taking my medicine and seeing her 4 times a year to monitor my eye disease. Then a little over a year ago I decided I had enough and I just stopped going.

Life continued onward then COVID-19 hit. I knew I should have taken better care of myself and as more time passed the guiltier I felt. To make myself feel better I’d say things like maybe the doctors were wrong and I didn’t actually have glaucoma and the only way to prove it was to stay away. Another part of me was far more afraid of catching COVID-19 than losing my residual eyesight and I felt this justified staying away.

By the time I’d gathered the courage to make an eye appointment, it was November 2020. My eye pressures were off the charts coming in at 50+ in both eyes. To give you some perspective, normal intraocular pressure ranges 10-20.

The doctor left me in the exam room while she went to get some sample medications for me to try. When she returned she gave the two medicines to my son and told him if I didn’t take them I’d lose my residual sight. She explained to him that the increased pressure on my optic nerve was causing irreversible damage.

Where Things Are Now

Aside from eating a ton of crow, due to my decision, I still feel quite vulnerable at the moment. I suppose since I’ve embraced my sight loss, which is a tangible thing, it’s still hard for me to fully understand an invisible eye disease. Myopia, high myopia, macular holes, detached retinas, retinal hemorrhages, and cataracts all make sense to me. I seriously struggle to understand this silent thief of sight partly because it came out of nowhere. While my grandmother had glaucoma, I never showed signs of it until I began having other eye problems.

Today, I’m on three different glaucoma drops to manage my eye pressure and we still haven’t settled on the exact mix yet. Since November, I’ve tried five different medications; one I had to stop taking because the beta-blocker in it triggered my asthma, two others were too costly. I’m hopeful that during my appointment on Thursday that the medicines I’m taking now work and are affordable.

If there were any doubts left about my diagnosis, they dissolved by an answer to a question. I asked my doctor what degree of sight I had remaining because I always hear my friends talk about their percentage of vision. She told me that since I have no central vision and now my peripheral is affected by glaucoma, there really isn’t a way to measure my field of vision. I’m still processing this and can only say I will to the best of my ability do what I have to do to keep the sight I have left.

I encourage readers to take your glaucoma diagnosis seriously, to find out all you can about it, and adhere to your treatment guidelines and schedule. Ask questions of your doctor and press for clear answers. Also educate your doctor as to the critical importance of learning skills to live with vision loss and referring patients for vision rehabilitation services so that regards of what happens with their vision, they can live full and productive lives.

Additional Information

Your Eye Condition