By Peggy Chong

Editor’s note: in honor of Black History Month, we are sharing this post by Peggy Chong, aka The Blind History Lady, who received the prestigious Dr. Jacob Bolotin award from the National Federation of the Blind (NFB) in 2018 for her work on the “Blind History Lady Project.”

For years, I have researched the history of blind people of the United States and realize how little I still know. Over the past seven years, I have sent my subscribers stories of blind persons of color, telling their stories. When researching our blind ancestors of color, the same issues of tracing our blind ancestors apply to those of the sighted ancestors of color, maybe even more so.

Persons of color, Black, Native American, Asian, and Hispanic, have been treated differently than the white population when gathering data for public records such as the U.S. Census. Sometimes, a last name was not recorded, or recorded incorrectly, as the census taker did not understand the culture or language. In researching my husband’s family tree, I found many women listed with the first name of “Shee.” In Chinese, “Shee” is the equivalent of Mrs. In some cases, a nickname of a person of color was recorded, rather than their formal name, necessitating some creativity on the part of current-day researchers and genealogists.

I have found that some blind relatives in all races did not even make the census data records. If a child was away at a school for the blind, they might not have been recorded in the family group by the census taker. Some schools and institutions did not record accurate information in their census data. Too many of our blind ancestors show up in a school for the blind or industrial home for the blind record, with missing or severely limited descriptive information.

Yet, we have stories from other sources about our ancestors such as the following:

Otho Jones—1862-1942. Born in Maryland the son of free Black farmers. At age five he was blinded when lye splashed into his eyes. He was sent to the Maryland School for the Colored Blind. Otho learned to read and write in raised print and make brooms. Later he learned to read and write in braille.

After school, Otho worked jobs such as, working tobacco fields, loading beer kegs for a brewery, chopping wood for farmers and more. Later in life, he sold newspapers on the streets of Hagerstown. None of the jobs made him wealthy, but he was self-supporting much of his life.

Otho was well informed. He could read, write, and discuss articles in the newspapers with his customers. Unlike many fellow sighted parishioners, Otho could read the Bible for his church groups. Given his knowledge of current affairs and politics, Otho encouraged his friends and church members to register and vote.

![Photo of John Langston Gwaltney. Oral History Association. [John Langston Gwaltney], photograph, 1981 University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Digital Library UNT libraries special collection.](https://aphconnectcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/metadc953342_m_UNTA_HM12-180-103_01.med_res-216x300-1.jpg) Photo of John Langston Gwaltney. Oral History Association. photograph, 1981 University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Digital Library UNT Libraries Special Collection.

Photo of John Langston Gwaltney. Oral History Association. photograph, 1981 University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Digital Library UNT Libraries Special Collection.

John L Gwaltney (1928-1998)

Born into a Black family that valued education and taught John to explore and question, he earned a BA from Upsala College in 1952, and an MA from the New School for Social Research in 1957. John did his dissertation on river blindness among the Chinantec-speaking people in Oaxaca, Mexico, earning a PhD in 1967.

In 1971 John accepted a professorship at Syracuse University where he focused his attention on the lived experiences of Black people in the United States. His influence on his students is noted in their tributes to him across the internet.

John retired from teaching in 1989. During his career, he also found time to work on projects for the Smithsonian, the New York State Creative Artist Public Service, the New York Council for the Humanities, and several National Science organizations.

John was an author of at least three books and numerous peer-reviewed journal articles exploring Black America. He was an artist, working in wood. Much has been written about him and he deserves a much closer look.

George Jackson—1928-1995. Among other things, George Jackson was Assistant Director of the Newark Manpower Training Skills Center in New Jersey. He taught psychology at New York University, was a professor at Howard University, a professional saxophone player, a prison psychologist, and conducted special research in the area of narcotic addiction.

Known as “Downbeat Jackson” from his early music days, he lectured his two-hour classes without notes, committing his lectures and subject material to his fantastic memory. Most of his students remained riveted to his topic.

In a 1982 article by Lucy Starr Norman of The Washington Post, George recalled how he’d broken his ankle roller skating. He shared that when his students learned how their professor ended up on crutches, he’d overheard a conversation that made him laugh for years to come. He overheard one student expressing concern that George (a blind man) was roller skating when he was injured. That’s when the second student corrected the first by noting that the problem had “nothing to do with whether he [George] can see. He’s too damn old to be skating.”

George told The Washington Post reporter, “You’ve got to be able to take these things that happen to you, and you’ve got to find the joy and humor in them.”

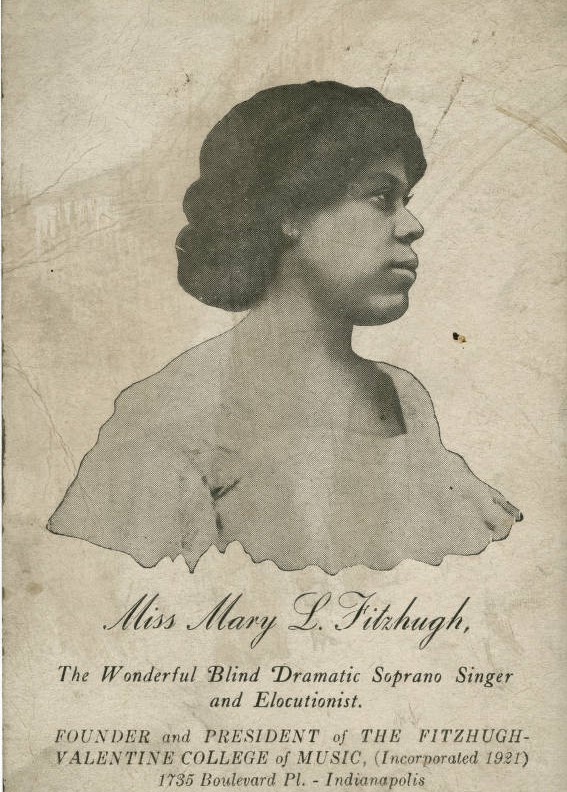

Mary Fitzhugh (about 1880-1945)

Blinded in her teens, Mary attended the Missouri School for the Blind. After graduating, she pursued a career as a classical singer, but found she was too Black for some of the white theaters, and too White for some of the Black civil rights advocates and audiences.

Mary moved to Indianapolis sometime about 1917 or 1918, married John William Valentine, and opened the Fitzhugh Valentine College of Music in August 1919. It was the first music school for “Colored” people in the state of Indiana.

Portrait of Miss Mary L. Fitzhugh (Photo compliments of the Indiana Historical Society)

Portrait of Miss Mary L. Fitzhugh (Photo compliments of the Indiana Historical Society)

The first few years were hard. Mary was teacher, administrator, recruiter, organizer, bookkeeper, and secretary.

She taught music to students who went on to have distinguished careers, such as Charles Amos, who after completing several years of training with Mary, became a teacher at her college and built his own career. Emily Raspberry

Emily Raspberry (1915-1988)

Born in Alabama and blinded after a severe bout of the flu during the pandemic of 1918, she was not admitted to the Alabama School for the Blind for the Colored until the age of twelve. During her first year at the school, Emily quickly learned to read and write braille and caught up to her peers.

Upon returning home for summer vacation, Emily found her mother gravely ill. She died just hours after Emily return. Within a week, Emily was moving to West Virginia with a half-sister, her world upended.

That fall, Emily was enrolled in the West Virginia School for the Deaf and Blind for the Colored. This school offered three times the reading material and classes than Alabama provided. She graduated about 1932 and found scholarships to The West Virginia Colored Institute – now known as West Virginia State University, one of the nation’s original Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Emily may have been the first Black and blind woman to graduate from the college.

Emily took a position at the school for the Colored blind while continuing her education, receiving a master’s degree. When the schools for the blind were desegregated, Emily was one of only three teachers who transitioned to the former school for the White blind in Romney, West Virginia, few colored students transitioned, but those who did, were pleased to find Miss Raspberry there.

Miss Raspberry was said not to have made any close relationships with other staff at the school, but former White and Black students told stories of Miss Raspberry paying their way to movies, plays, and musical concerts. She provided students with advice for life they remembered long after her death.

Learn More

If you wish to read more in-depth stories of our blind ancestors, subscribe to my mailing list by sending an email to [email protected]. Also, check out Peggy Chong’s website at TheBlindHistoryLady.com.

The Museum of the American Printing House for the Blind is another great source of information about people, both blind and sighted, and events that have made the world a more accessible place. The APH Museum is dedicated to removing barriers and promoting tolerance and fairness.